Splitgraph has been acquired by EDB! Read the blog post.

It took 10 minutes to add support for DataGrip to Splitgraph

We discuss a philosophy of not breaking existing abstractions that we think explains the success of tools like Docker and Git and how we applied it to Splitgraph, helping us launch with multiple integrations.

Splitgraph is a tool that makes it easier for data engineers and data scientists to build, query and share datasets. It uses PostgreSQL as a foundation and is compatible with anything that works with PostgreSQL.

In this article, we'll discuss a philosophy of not breaking existing abstractions that we think explains the success of tools like Docker and Git. We'll also talk about how we applied it when we designed Splitgraph and how it let us launch with first-class support for tools like DataGrip, dbt, Metabase or PostGIS.

Integrating DataGrip with Splitgraph

Shortly before we went public with Splitgraph, we were figuring out any interesting integrations we could launch it with.

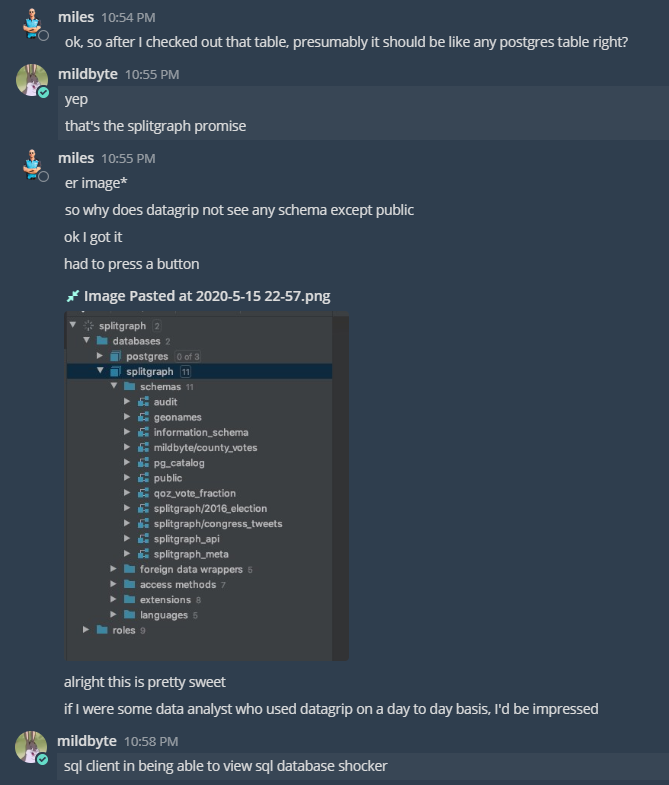

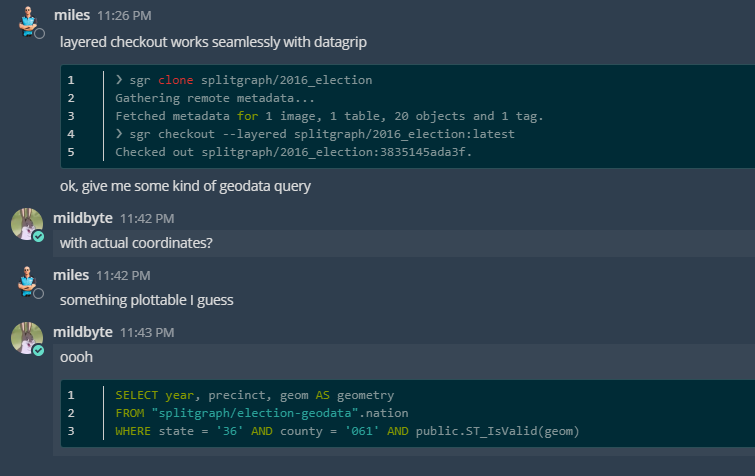

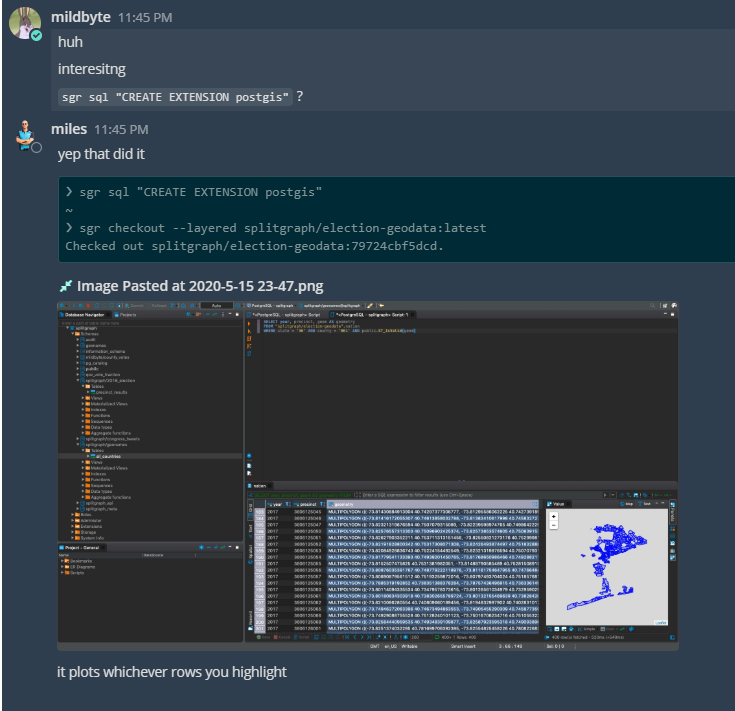

Here's a play-by-play of us realizing that we didn't need to do anything to get JetBrains DataGrip to work with Splitgraph's layered querying or PostGIS-enabled Splitgraph images:

This was kind of anticlimactic. Integrating other clients took us about half a day. Building an example of Splitgraph working with dbt took one day.

We think that this is due to a big design decision we made in Splitgraph's early days.

Isn't it cool to write a database?

When you want to build a feature for working with data, you have two options.

The first option is that you can build a brand new database from scratch and reimplement everything that makes a database a database. Most of these things won't be related to your core feature set that makes your product different. But, by building from the ground up, you might be able to squeeze out that extra bit of performance or make big unconstrained architectural decisions.

Dozens of new database systems get released every year. Some have fast columnar storage. Some do versioning. Some work with timeseries data. Some operate on live data pipelines. Writing a database is indeed very cool.

Imagine writing your own query planner or a parser. Figuring out a format to store the data on disk. Coming up with some indexes you could add to your database. Transactions are also in the pipeline. You'd use MVCC or something. Durability, eventually. You should try to be compatible with a wire protocol as well.

This is fun and technically challenging work. Engineers love building things and "built a database" is a great entry to put on your CV.

But then, the problems start.

- The database segfaults if some application calls something in a weird way.

- People ask you to implement boring things, like support for Kerberos, or replication, or that one specific JOIN that they rely on, or stored procedures, or triggers.

- Somebody fires a bunch of queries at your database and finds corner cases that completely break it.

Is the tradeoff of adding all these features and bringing your database to feature parity with existing offerings worth it?

Isn't it cool to not write a database?

Splitgraph chose the second option.

From the very beginning, we knew that we didn't have the staff, the time or the funds to build a new database. Besides, building a new database felt contrary to everything we knew about computers and existing successful tooling. After all, "we do not break userspace":

- Git adds versioning to files by working on top of an existing abstraction (the filesystem) and enhancing it. It doesn't force users to use a new filesystem.

- Docker containerizes applications by using the tools provided by the kernel itself. It doesn't force users to use a new kernel.

IDEs, editors, compilers and other applications don't need to be aware of these tools to benefit from them. They enhance existing abstractions instead of breaking them.

Enhance abstractions without breaking them

For Splitgraph, we chose PostgreSQL as a foundation to build on. A Splitgraph engine is a PostgreSQL instance with some extra custom extensions. Most of Splitgraph's operations use the SQL standard. After you check out a Splitgraph image, it's just a set of ordinary tables that you can use all features of PostgreSQL on.

When we realized that there should be a way to avoid the checkout step, we wrote a layered querying plugin. Layered querying is a foreign data wrapper, which is a first-class PostgreSQL feature. The database takes care of all query parsing for us. We only need to figure out how to give Splitgraph tuples to it fast enough. We could now experiment with hotswapping data into Splitgraph on the fly or speeding queries up. And, we would still support any PostgreSQL statement, past, present or future.

When we wanted to improve Splitgraph's data pushes and pulls, we started storing Splitgraph objects in cstore_fdw files. It's a columnar store that offers low IO load and fast performance for OLAP workloads. Splitgraph can query cstore_fdw files directly without having to load them into the database. This meant that we could now store them on S3 and swap them in and out of local cache when we needed to use them.

When we got ambitious and wanted to try PostGIS, it just worked. Our REST API, powered by PostgREST, would return geospatial data as GeoJSON. cstore_fdw is compatible with custom PostgreSQL types, so it would store geometry columns without problems.

Conclusion

DataGrip, dbt, Metabase, PostGIS and anything else in PostgreSQL's vast ecosystem of clients, tools and extensions aren't (yet!) aware of Splitgraph.

Despite that, it gives superpowers to all of them.

Imagine building a dbt model on versioned data to perform what-if analyses. Or, imagine using Metabase to plot data from remote datasets with a small local cache space.

Splitgraph enhances existing abstractions without breaking them. All existing PostgreSQL clients, tools and extensions are compatible with Splitgraph. We collect examples of the most interesting integrations in our documentation.

If you're interested in learning more about Splitgraph, you can check our frequently asked questions section, follow our quick start guide or visit our website.